If you’re a reader of a certain age, you may remember waking up very very early in the morning – far too early for your mother’s liking – climbing out of bed and heading to the front window of your house. When all was quiet and nothing else moved in your street, perhaps you stood there in the chill waiting. Waiting for the reassuring sound of the clip clop of a horse. Before long, the shaggy head of a Clydesdale came into view, pulling behind it a cart loaded with the day’s milk deliveries. The ‘milko’ would then place your family’s order of milk in bottles on the front step. Then the clip clop would start again and the milko would move on to the next house. Before the sun had risen, in your child eyes, the day had already begun.

In Ashburton and Glen Iris, this delivery of milk came from the Ashburton Dairy. It’s long gone now but it stood at 333 High Street on the corner of Stocks Avenue for over 40 years.

Ashburton Dairy and the milk distribution facilities, a barn and modest-sized house, plus pasture for the Clydesdale horses were all owned by the Stocks Brothers, descendants of one of Ashburton’s earliest pioneers.

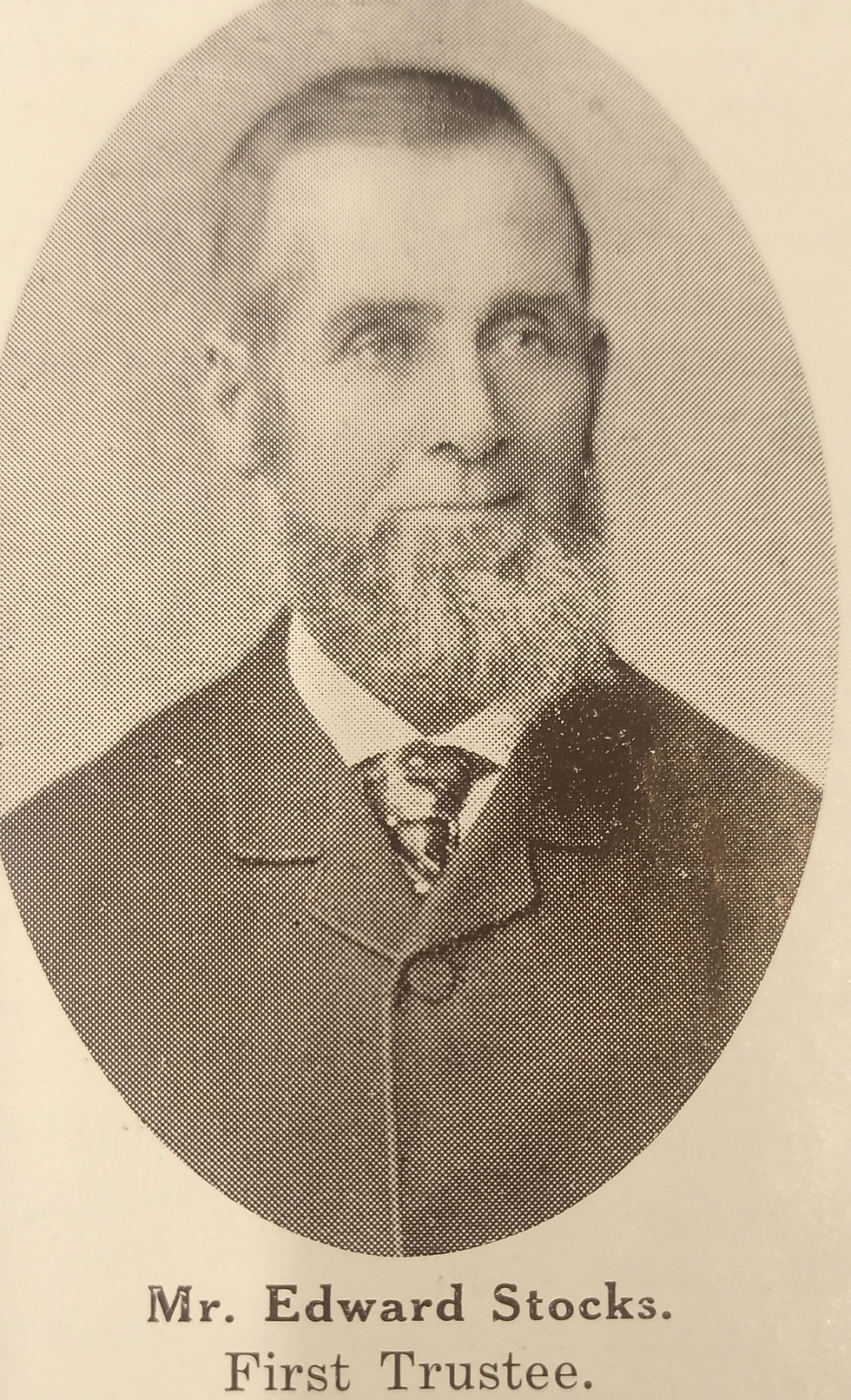

Edward Stocks

Even by the 1960s, the Stocks Brothers could trace their Ashburton heritage back almost a century. They were the grandsons of one of the first English landowners in Ashburton: Edward Stocks.

Born on 25 February 1829, Edward Stocks arrived in Melbourne from Pocklington, Yorkshire on a ship called Lord Ashburton. It was 1850 and he was 21 years old.

Melbourne at this time was more a filthy and smelly shanty town than a city. Soon afterwards, Edward purchased the rolling pasture land between Boundary (Warrigal) Road and High Street that eventually became part of Ashburton. It had previously been owned by John Gardiner but it’s not clear if Edward bought it off him or another early settler.

Edward Stocks built a house at the south-eastern corner of his land on the site now occupied by Holmesglen Station. From that point on, his profession was documented as ‘Market Gardener’.

Origins of the Ashburton name

It is sometimes thought that Edward Stocks was responsible for giving the area the Ashburton name because of his connection to Lord Ashburton. He was known to use the name of the ship he arrived on in his correspondence as his address. However, Stocks had no interest in local political affairs and was unlikely to have exerted his influence in this way. Although it can’t be proven outright, it is more likely the ‘Ashburton’ name came from the suggestion of City of Camberwell Councillor Dillon. In the quest to rename the Outer Circle Line’s Norwood Station, Dillon suggested the name Ashburton, after a picturesque hillside he knew in County Cork, Ireland.

The Stocks Family

Three years later, Stocks married a young woman called Ann Westoby (or Westby/Westerby - all three appear in the records). There is no record of her birth in Melbourne. Since this was not a time when Melbourne was populated by that many available women, it’s quite possible Edward already knew Ann back in Yorkshire and sent for her. He married her soon after she disembarked from her ship in 1853. Within two years, Ann and Edward welcomed their first child Charles. Sadly, he died at five months old. Two years later, their second son John Edward arrived. He was followed by another Charles (1860), an ‘unnamed male’ in 1863 (possibly James?), Walter (1865), Ann Elizabeth (1867), Mary Hannah (1869), Alice Maud (1872) and William Byass (1874).

By William’s birth, Edward and Ann Stocks had become prominent local landowners. Department of Lands records showed the Stocks family also held grazing rites over all the land from Glen Iris Road to Summerhill Road between High Street Road and Back Creek.[1]

The first trustee of Glen Iris Methodist Church

Edward Stocks was a well-regarded and upstanding man in the local community of gardeners and land-owners. He became the first trustee of the Glen Iris Uniting Church on Glen Iris Road and taught Sunday School there for 16 years. According to the church history:

‘in his declining years, the younger generation of the church paid regular attention to him. Many have hinted that his many kindnesses were not known to all men. During the lean days of the church, the accounts were always paid and Mr Stocks knew the secret.’[2]

He died in 1910, five years after Ann.

Most of their children remained in the area. Their sons followed their father into market gardening. Their daughters remained active in the church as organists and married local men. Three of the four sons of Edward and Ann’s son Charles and his wife Rosina McEwan: Charles Leslie, William, and Walter; became the Stocks Brothers who moved the family agricultural business into dairying. Charles and Rosina’s eldest son Edward had already died in 1920. Their daughter Agnes Ann never married, so it’s possible she was involved in the business too.

Milk in early Melbourne

In the beginning of colonial Melbourne, everybody got their milk from a local cow they kept in their yard. She was fed with whatever leftover scraps of food were available and any grass she could scavenge for herself. Responsibility for milking, creating, and producing dairy products lay with the women in the family. Should a woman prove particularly skilful and knowledgeable at dairy production, she often formed a cooperative small business creating and supplying milk products from the milk of all the neighbours’ cows and selling the products back to them.

As it is today, milk was a highly perishable product. Dairying was a very labour-intensive process, fraught with the challenges of maintaining hygiene and cleanliness. So while these small-scale dairy production businesses provided a welcome source of income to the family, the inability to preserve the products for any length of time stymied any ambitions of business growth for many years.

As Melbourne expanded and more housing and industry development occurred, there was no longer room for the family cow in inner city homes. They either disappeared or moved onto reserves and town commons.

City of Camberwell minutes of meetings are riddled with reference to cows and livestock wondering onto local reserves at Ashburton Park and Burwood Reserve and getting in the way of cricket and football matches until well into the 1930s.

Of course, urban growth did not mean there was no longer demand for milk. Fortunately for Melbourne’s milk enthusiasts, enterprising farmers had long ago realised that Victoria had an ample supply of cool green pastures perfect for the production of superior milk, butter and cheese. Local dairies sprung up around suburbs and towns.

Refrigeration arrived in the 1880s and this coincided with the expansion of the railways. It was now more viable to house larger herds of dairy cows outside the city and transport the milk from the fertile pastures of the foothills of the Dandenong Ranges by train into the town or city for production into dairy products like butter, cheese, and cream.

Yet time was still of the essence. Homes did not yet have refrigeration, so daily milk delivery was still the safest and most cost-effective way to get milk to customers.

The ‘milko’

Enter the milkman, his horse and a cart. In Australia, he became known as the ‘milko’ because Australians never met a word they couldn’t shorten and/or add an ‘o’ to. The milko carried the milk in a bulk container and to collect their milk, people used whatever container they had available. Eventually standardised bottles arrived but this did little to apprehend the contamination challenges. By the 1920s, sufficient technological advancements had occurred, including the inclusion of steam engines and electricity in the manufacturing process, to improve the viability of locally manufactured dairy products.

By the 1930s, scientists knew that milk was a significant source of calcium (or ‘lime’ as they called it before someone decided that it might be confused with the fruit and/or the building material) that aided children’s growth, bones and teeth. A local ‘Drink More Milk’ Campaign ran in the 1930s to encourage milk consumption ‘because the bones are constantly wearing away little by little and must be replaced.’ Demand for milk and milk-based products escalated.

When an escalating demand for milk combined with a rapidly urbanising area like Glen Iris and Ashburton, opening a local dairy was suddenly a very viable business opportunity. Since dairying in post-WWI Melbourne still carried significant contamination risks, a well-known, local and upstanding name like Stocks reassured local people of the reliability of an Ashburton Dairy under their control. As you can see from this aerial photograph from 1945, it also helped that the Stocks family still owned a large expanse of pasture and land near Ashburton’s growing shopping strip.

The Ashburton Dairy

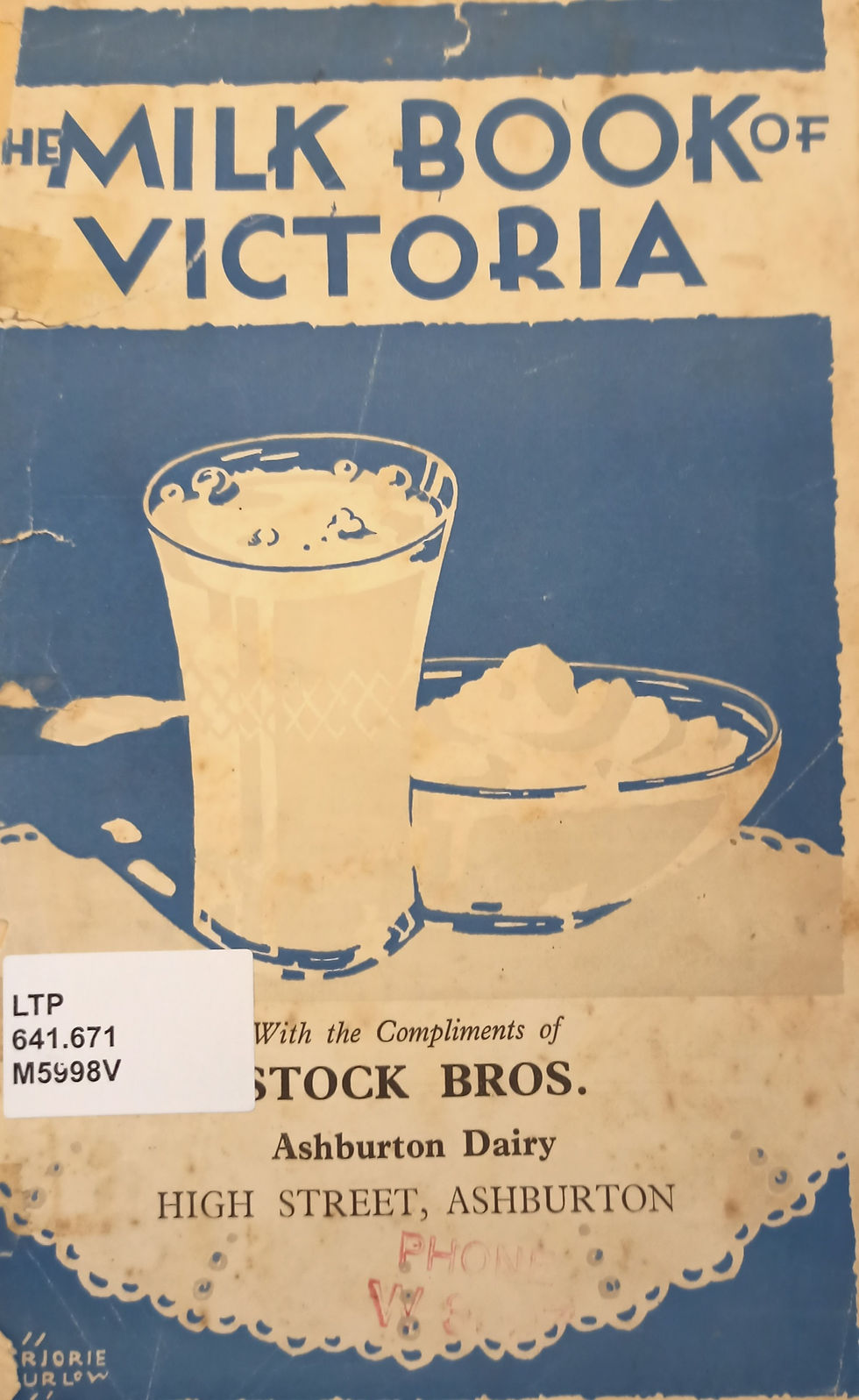

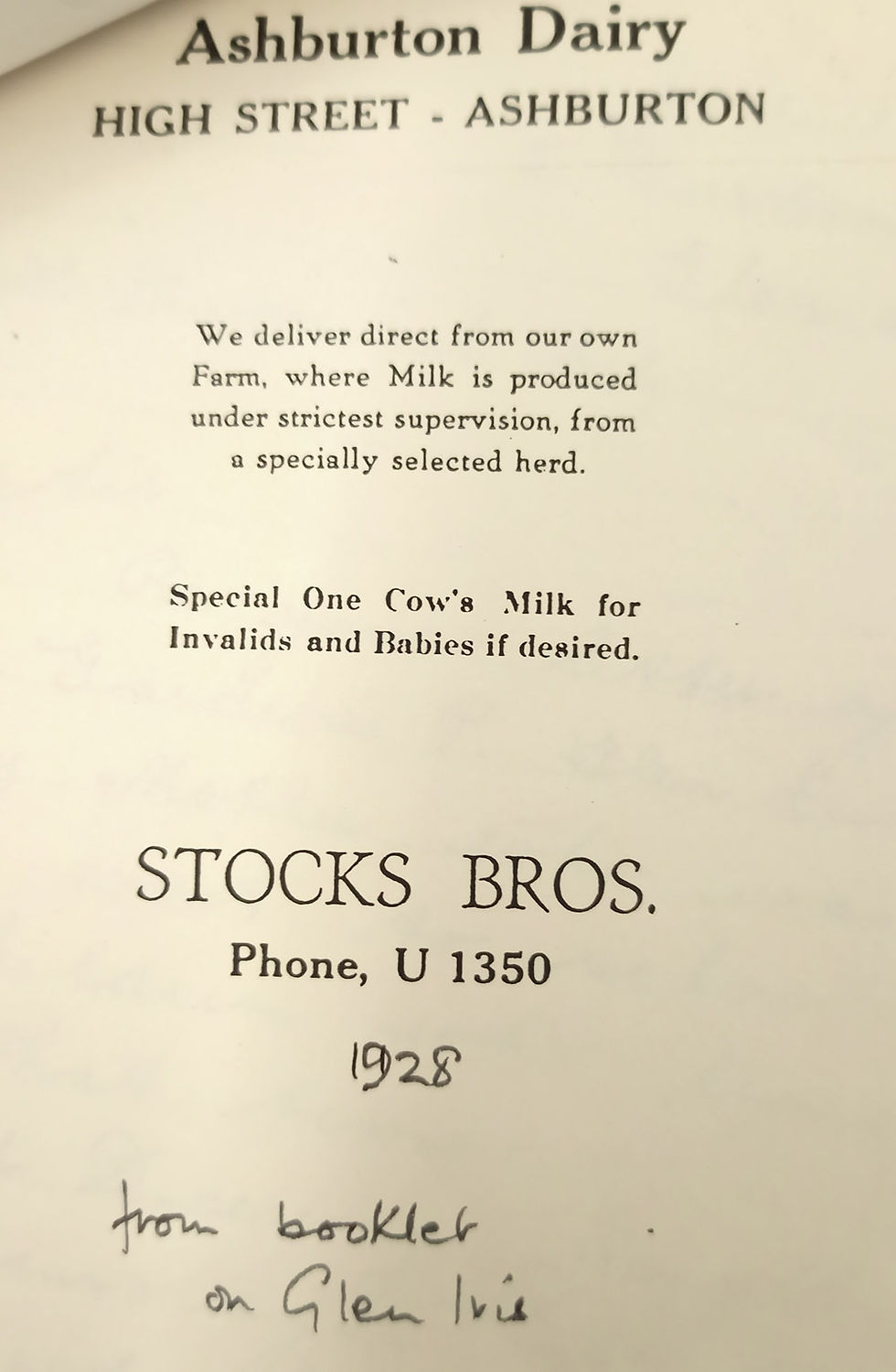

Exactly when the Dairy was built and opened is not entirely clear from the scant number of records I can find about it. The City of Boroondara’s Thematic Environmental History put the year as around 1937 after the first listing of it in the Sands and McDougall business directory. Yet a published history of Glen Iris from 1928 contains an advertisement for the Dairy (pictured above) under the management of the Stocks Brothers, so it seems they owned it far earlier than that.

In addition, a 1926 newspaper article from the Argus indicates that a Dairy was on High Street already. Arthur Baker, who contrary to his name was actually a dairyman, was charged in Camberwell Court in December 1926 for having his dairy in an unsanitary condition. The inspector went on record to say it was ‘the worst case I have seen’.[3] The article describes how the milk, walls and ceilings were covered with flies and the entire establishment had exceedingly poor ventilation.

So it seems quite possible that the Stocks Brothers took over the shamed Baker’s dairy business. This would explain why their early advertisements took pains to emphasise ‘sanitary supervision’ and the ‘quality of the home-grown herd’.

Deliveries and Ashburton life

The Stocks Brothers enjoyed a local monopoly on milk and dairy in Glen Iris and Ashburton for the next four decades. Their delivery jurisdiction stretched as far north as Hartwell Road, east to Glen Iris Road, west to Warrigal Road and south to High Street. At some point after 1945, they must have sold off a large portion of their land to the Housing Commission. From the aerial photograph above, you can see there was still land available to maintain a herd of cows near the Dairy on Stocks Avenue.

According to people I have spoken to who lived in the area at the time, Ashburton Dairy used a horse and cart for deliveries until sometime in the 1960s. People today still remember going with their mothers to pay the milk bill at the Dairy and patting the Clydesdale horses in the pasture.

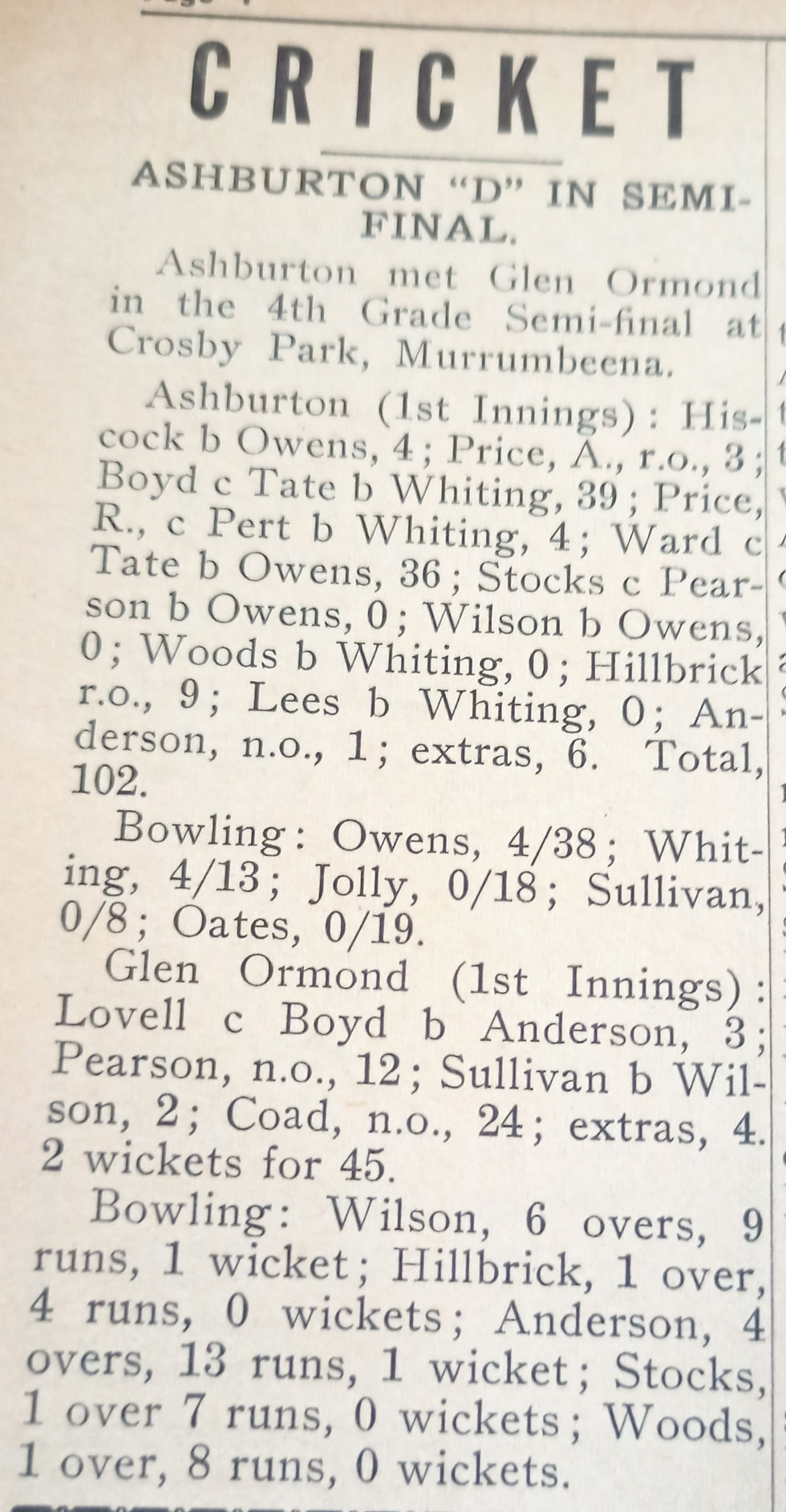

In the tradition of their grandfather, the Stocks Brothers maintained support for local community endeavours. In 1941, they donated funds to the Baby Health Centre on Welfare Parade and their families were involved in the Ashburton Cricket Club well into the 1970s.

The end of the Dairy

Eventually, progress arrived in Ashburton through improvements in refrigeration and grocery stores supplying milk. Most people now had a refrigerator in their house and the need for daily milk deliveries reduced. A local dairy became increasingly economically unviable.

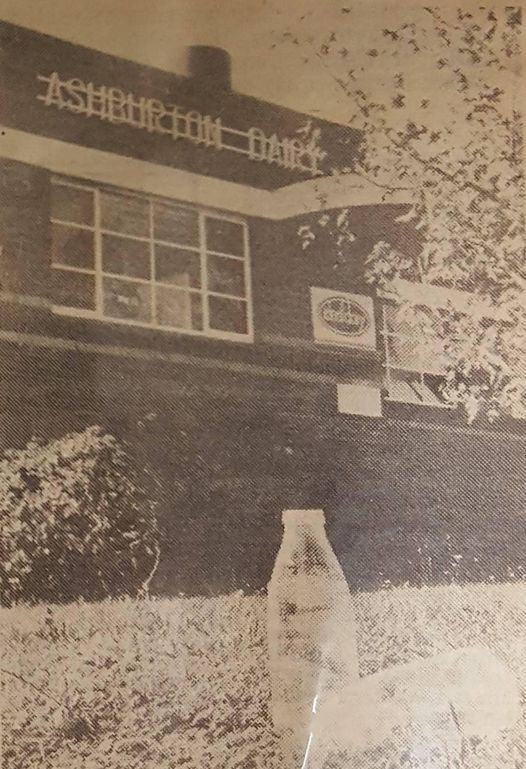

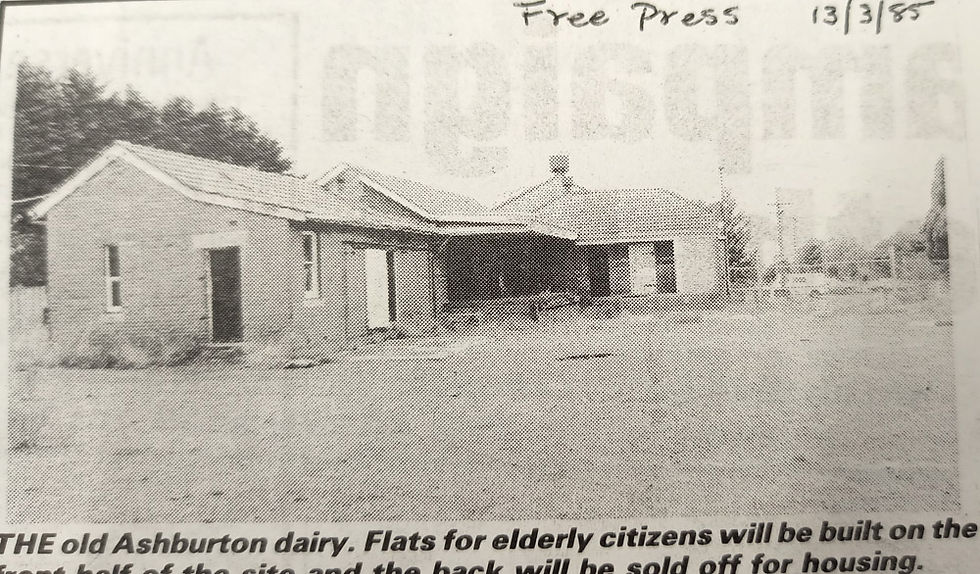

The Stocks Brothers were also getting on in age. Charles died in 1960, William in 1968 and Walter in 1970. The land around Stocks Avenue was sold off and sub-divided. The Ashburton Dairy buildings grew derelict. This photograph below shows the 1930s art-deco style building had gone by 1985.

Young vs Old: what to do with the old Dairy site?

At some point in the early 1980s, the Ashburton and District Senior Citizens’ Welfare Association began a campaign to ask the City of Camberwell Council to purchase the Ashburton Dairy site and build housing for the elderly. The site was now the last large tranche of vacant land available in Ashburton.

However, they were not the only local entity with an eye on the land. The Alamein Community Youth Support Scheme, the only youth-oriented facility in the entire area, needed new premises and sought to lease the house on the Dairy site. But they were over-ruled and Camberwell Council purchased the land from the Stocks family with the intention of providing housing for the elderly.

The Council demolished the last vestiges of the now vermin-infested Ashburton Dairy. In collaboration with the Ministry of Housing, 14 villas for the elderly were built on the old site.

The Stocks Brothers dairy products had helped local residents grow strong and now the site would house them in their final years.

All that remains from the days of the Dairy are the large conifers that line the dividing fence with Ashburton Park and a multitude of Stocks family descendants.

References [1] Lee, Neville, 'An Extended Version of the Talk on Ashburton through the Ages Presented at the Ashburton Library,' 5 September 2014. 10. [2] Church, Glen Iris Methodist, "Three Score Years and Ten": A Short Souvenir History of the Glen Iris Methodist Church (Unknown publisher, 1932). 26 [3] "Dirty Dairy," Argus, 17 December 1926.

Comments